Grammy Award-winning soloist and Māori musical instrument specialist Jerome Kavanagh Poutama is set to enchant Thessaloniki with the ancient sounds of Taonga Pūoro. On Friday, he will perform alongside the Thessaloniki State Orchestra, blending the spiritual essence of Māori music with classical symphonic sounds.

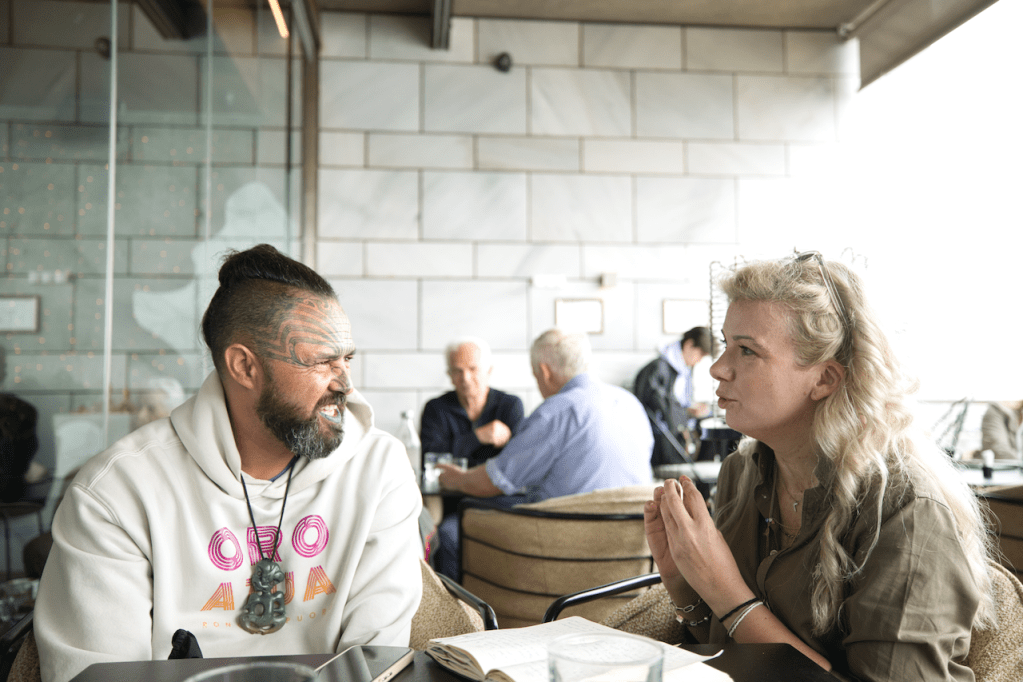

Ahead of his highly anticipated concert, he speaks about the deep-rooted cultural significance of Māori instruments, the powerful fusion of indigenous sounds with classical compositions, and the universal connection that nature’s music fosters across cultures. In this exclusive interview, Kavanagh shares insights into his journey with Taonga Pūoro and his creative process, offering a glimpse into what audiences can expect from this unique musical experience.

Διαβάστε τη συνέντευξη στα Ελληνικά εδώ.

Interview: GEORGIA SKONDRANI

Thank you so much for coming to Thessaloniki and bringing your amazing music to us. First of all, can you tell us what we can expect to hear at tomorrow night’s concert? How do you think your music will resonate with Greek audiences?

Jerome Kavanagh Poutama: What I am bringing to the concert is all about traditional Māori musical instruments. They come from an ancient period of time, so they are very old—older than some classical instruments, I guess. What they bring us is the sound of nature, and the beautiful thing is that when you mix it with classical music, it creates something new, which is quite beautiful. I think the people of Thessaloniki will hear nature itself. Nature is universal—the sounds of the ocean, the birds, and the forests. Hopefully, they will feel nature in the music and connect with it.

You were first introduced to Taonga Puoro at 16 by your aunt. Can you share the moment you first connected with these instruments and how it shaped your musical journey?

Actually, my first introduction was even earlier. When I was eight years old, my grandmother gave me my first traditional instrument. Then, when I was 16, my aunt gave me another one. That was when I truly started to think about these instruments seriously.

My real training in music came from growing up in a rural area, spending a lot of time in nature—playing in the forests and by the river. I used to climb a particular tree and listen to different birds, who are known for this songs, the kōri mūkoe. As a toddler, I would try to mimic the birds’ sounds with my voice. That early connection with nature shaped my entire approach to music. Because it’s where the music comes from.

As a specialist in Māori musical instruments, what do you find most powerful about their sound and cultural significance?

Well, I think in terms of cultural significance, we use our music a lot in ceremonies. We use it when a baby is born, and during pregnancy. We also use it when someone passes away, during a funeral ceremony, which we call Tanya Hama. We use it when welcoming guests to our area, so music plays a significant role in our ceremonies. One of the most original purposes of this music is to help maintain the health of our people and ourselves. We use it in a more therapeutic way, I guess.

That’s how our ancestors used sound—to help people when they were sick or unwell. But also, music was used to connect with the environment. We spent a lot of time outside playing, which is important. And then, the last part of it is entertainment—using music for performance. So, it’s a little different from music today. Now, music is more performance-based, but in its tradition, this music was primarily for ceremony, healing, and health.

How did you come up with the idea of combining modern music with Māori music?

Great question! I have a friend called Selena Fisher, and she wrote all the orchestral music. She composes for the orchestra. I spent time with her, playing all of my compositions that I draw from nature. In classical music, you go to school, study the greats, and learn music in that way. But for us, we spend time in nature—we play with nature, we listen—and that’s how we compose our music. The music comes from the land, the ocean, and the mountains. I shared those 20 years of compositions, created while walking in nature, with my friend Selena, and she wrote all the orchestral music around them. That makes it very different, and I feel like it might be a world-first collaboration in how these two musical traditions are brought together and heard.

Was it difficult to merge these two musical styles?

Yes, absolutely! But Selina did an incredible job bringing these two worlds together.

Will she be attending the concert?

She was supposed to come, but she’s still in New Zealand, unfortunately.

You won a Grammy for your work on Calling All Dawns, which brought Māori music to a global stage. What did that experience mean to you personally and culturally?

Winning a Grammy is huge—it’s the biggest music award in the world. But for me, the most important part was creating a song in the Māori language that was heard globally. We used an ancient proverb that speaks about the peacefulness of the ocean and spreading that energy to people. So that’s what that song is about. We used our traditional instruments in Wove Dead and so I think our song was unique because it was the only Grammy-winning track sung in Māori and featuring traditional Māori instruments, blended with classical music. So yeah, I mean it was a long time ago, I think we wrote it in 2007 or 2008, and it won in 2011—it was ahead of its time. But to bring our small culture to such a massive global stage meant everything.

That’s truly incredible. You brought your culture and music to the world in such a meaningful way.

Thank you! That’s right.

What advice would you give to young Māori musicians looking to follow in your footsteps and explore their musical heritage?

My biggest advice is to stay true to yourself and be authentic. In New Zealand, because we are a small country, we often look to Europe or America as kind of great thing, but then we also forget about our own greatness. The key to my success has been staying true to who we are, without trying to be something else. I think audiences in Europe, like in Greece, appreciate authenticity. They don’t want to see me trying to be Greek—they want to experience Māori music and culture as it truly is. Another important thing is spending time in nature. Many young musicians ask me to teach them, but I always tell them to take their instrument and sit in the forest. That’s where the greatest teacher is—not me, but nature itself.

Are young people in New Zealand interested in traditional Māori music?

Yes, there has been a big cultural renaissance in New Zealand, especially in language and music. However, traditional Māori instruments are still in the process of revival. So we have a lot of music, that’s kind of pop music but in our language. And I feel like, once again, it’s about coming back to being authentic—just doing your own thing, you know, being yourself.

In today’s world, being authentic is more important than ever, don’t you think?

Absolutely. Staying true to yourself is what truly matters.

How do people react when they hear your music for the first time?

It’s been amazing. At our first rehearsal, the musicians were in tears. They told me they had never heard anything like it before, and they could feel the music deeply. Originally, we were supposed to perform second in the concert, but the conductor, Miltos Logiadis, changed the order. He said, “We can’t play anything else after this. It has to be the final piece.” That was a huge honor.

That’s incredible! It must feel amazing to see people connect so emotionally with your music.

Yes, it’s beautiful. Seeing people cry, share their feelings… And some of the older musicians, they said that they never heard this kind of music ever before and they haven’t felt like this, so it’s perfect. That’s what music is all about.

Thank you so much for your time, and for sharing your incredible music with us.

Thank you! It’s been a pleasure.

Photographer: Nikolaos Tsiolis